Equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) is the most significant equine herpesvirus in terms of equine health and economic impact to equine industries worldwide. EHV-1 is believed to have co-evolved with horses over millions of years. This co-evolutionary relationship resulted in the development of a life-long carrier state in a high percentage of infected horses. This involves viral latency (silent infection) of various sites (trigeminal ganglia in the central nervous system, respiratory lymphoid tissues, and CD3+ T lymphocytes in the blood). Latency ensures perpetuation of EHV-1 by serving as a virus reservoir for infection and dissemination in susceptible populations. It is no wonder that EHV-1 is ubiquitous in horse populations worldwide.

A wide range of clinico-pathological syndromes are attributed to EHV-1 infection. EHV-1 infections can result in respiratory disease in foals and two to three-year-old horses in training; contagious abortion in mares; congenital disease and death in foals infected in utero; and neurologic disease (myeloencephalopathy) in horses of variable ages, especially older animals. Less frequently encountered EHV-1 diseases include: retinouveitis in foals; fatal generalized peracute disease (pulmonary viscerotropic infection) in young adult to older adult horses; intestinal ganglionitis and impaction; and scrotal edema and loss of libido in stallions.

EHV-1 was implicated as the agent responsible for annual occurrences of “abortion storms” in the Thoroughbred breeding population in Kentucky at least as far back as 1933 and is widely acknowledged as the most significant cause of equine contagious abortion in many countries. Implementation of sound management practices and prophylactic vaccination of pregnant mares have, where practiced, greatly reduced the frequency of EHV-1 abortion storms. Susceptible mares exposed to EHV-1 late in pregnancy may carry to term, but give birth to a diseased foal that invariably succumbs from fulminant viral pneumonitis. Unless appropriate biosecurity measures are taken, there is a high risk that affected foals can serve as a source of infection through direct or indirect means for healthy foals and pregnant mares.

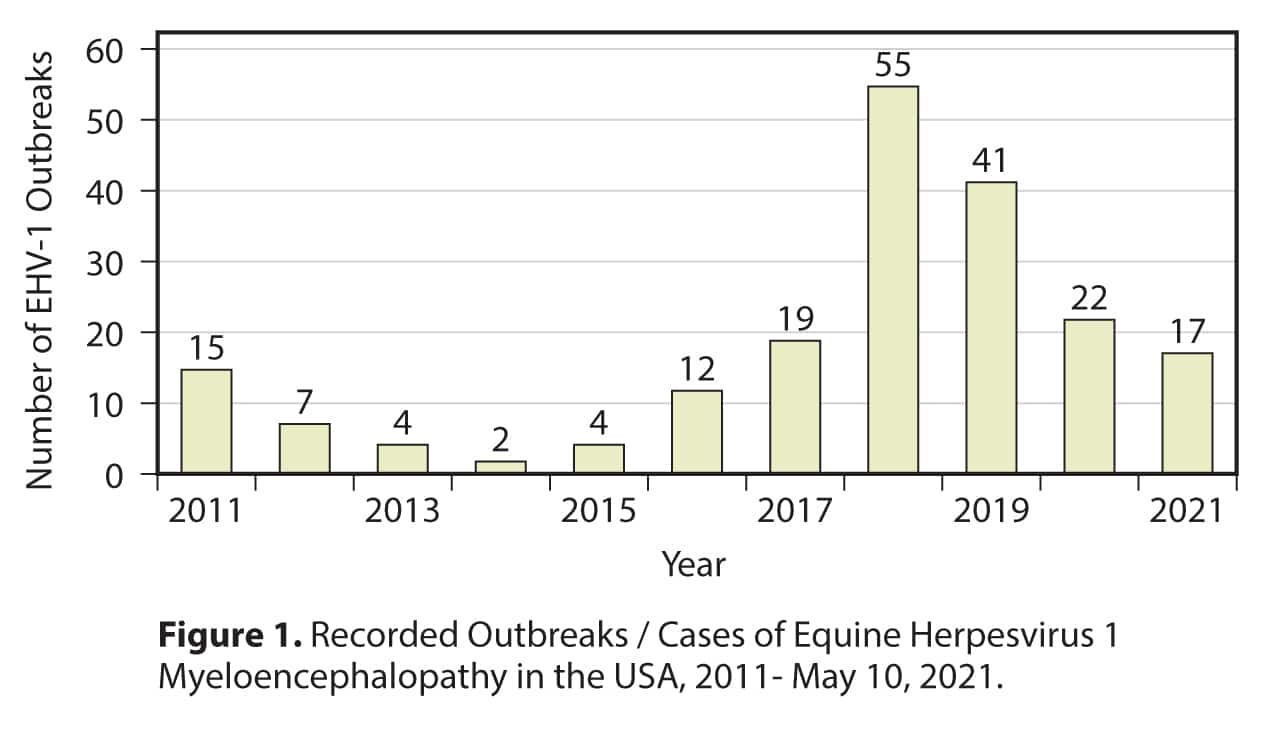

The clinical syndrome that has attracted the most concern in recent years is equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM). This syndrome has been recorded with increasing frequency in North America and Europe over the past 20 years (Figure 1). In 2007, the USDA designated EHM caused by a hypervirulent strain of EHV-1, a potentially emergent disease of the horse. EHM tends to be seasonal with increased case numbers in winter and spring.

A comprehensive biosecurity plan is critical to prevent and control outbreaks of EHM. Optimally, its aim should be to prevent the introduction of an equine pathogen viz. EHV-1 onto a premises, be it a farm or event venue (equestrian, racetrack, horse show), by whatever measures are considered appropriate and necessary. This is especially important when dealing with an EHM outbreak. In such a situation, the primary aim should restrict the spread of infection at the index premises/facility by quarantine of infected and exposed horses. Furthermore, every effort should be made to ensure that the outbreak is effectively contained and eliminate the possibility of virus spread to other premises/facilities.

Restriction of movement of exposed horses off an affected premises is crucially important, and failure to observe this precautionary measure carries a considerable risk of EHV-1 spread that can have very significant consequences. This was exemplified at the NCHA Western National Championship at Ogden, Utah in May 2011, when exposed horses departed the event and subsequently spread EHV-1 to 12 US states and two Canadian provinces. An analogous situation occurred at the CES Spring Tour in Valencia, Spain in February 2021. During the extensive EHM outbreak at this event, a significant number of exposed horses were transported back to their countries of origin. The outcome was calamitous, with multiple horses developing neurologic disease, some of which died or were euthanized.

Equine herpesvirus 1 remains a highly significant pathogen that has the potential to cause a range of clinical syndromes in the horse and can have considerable economic consequences for equine industries.

~ Peter J. Timoney, MVB, MS, PhD, FRCVS, Equine Disease Quarterly