As the private plane started to dive straight toward the earth in a violent thunderstorm, all equine veterinarian Dr. Huw Llewellyn could think was, “I just made it, and now I’m going to die.”

It was a real-life scene shockingly similar to the one in the movie Almost Famous where the members of the fictional rock band Stillwater finally trade in their beloved tour bus for a private plane and instantly find themselves about to crash in a thunderstorm.

In both fiction and reality, the protagonists lived to tell the tale, but Llewellyn — a man that once built an impressive eventing course on his property in Stayner, ON — has never forgotten his brush with death that encapsulated just how crazy his life became while being flown around the world to perform his ground-breaking palate surgery.

In the 40 years since he first performed his surgery on a Standardbred racehorse competing on the Woodbine circuit, the Ontario-based vet believes he’s done the procedure some 9,000 times on four continents on Standardbreds, Thoroughbreds, sport horses, Clydesdales, Hackney ponies and other breeds.

“I used to go to Italy every couple of months to do the surgery,” Llewellyn said. “Also the Meadowlands was the big [Standardbred] track when I started doing the procedure and I used to go down there every week or 10 days and would do some at the Meadowlands, some at Yonkers and some at Belmont ‒ so I’d be all over New York and New Jersey.”

Llewellyn graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in London, England, in 1971 and was initially interested in small animal surgery ‒ “although I loved horses,” he said. He came to Guelph, ON, in 1973 to do an internship in small animal surgery with the hope of landing a residency at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College (OVC). When the small animal position went to someone else, he accepted a similar post with large animals. Near the end of the decade, he left OVC to start his own practice solely working with horses.

“I used to do the soft palate surgery like everyone had done before – sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t,” Llewellyn said. “Then I thought, ‘If I could cut this muscle, it would allow the voice box to slide forward and be better.’

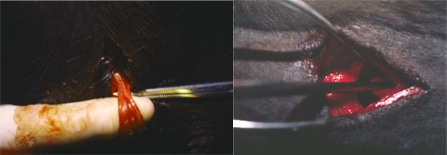

Cutting the muscles and trimming the soft palate.

“The first one I did, I was petrified. I didn’t know if the horse would be able to swallow or anything afterwards. I trimmed the palate a little bit on that horse and I remember the owner being there when I cut this little piece off his palate and he said, ‘I cut more off my toenails than you cut off there.’ I said, ‘I can cut more off, but I can’t stick it back on.’

The surgery to correct dorsal displacement of the soft palate is called sternothyroideus tenectomy, sometimes combined with a staphylectomy (cutting a small segment out of the soft palate.) “Sometimes I will just cut the muscle and leave the staphylectomy, especially if the horse has to race in a week,” he explains.

One of the biggest advantages of the Llewellyn Procedure is that it is a minimally-invasive, quick surgical technique that does not take the horse out of training. Even if unsuccessful, it does not make the horse any worse.

Forty years on, Llewellyn can’t remember the name of the Standardbred racehorse on which he first tried the procedure, but he does remember it went on to earn some $200,000 over the next three months.

“After that, the word spread like wildfire,” Llewellyn said of his procedure that takes no more than two minutes to perform and has helped equine athletes to breathe much better and thus perform much better. He believes his most successful patient was Tale of the Cat, a Thoroughbred he operated on at Monmouth Park.

Lexie and Huw.

“He was valued at $2 million before I did the procedure on him, then he went out and won the King’s Bishop Stakes at Saratoga and they sold half of him for $7.5 million. So, I changed his value from $2 million to $15 million and now he’s a stallion. I was down in Keeneland two years ago and I went to the farm and saw him. Justified is in one paddock and he’s in the other paddock. That was exciting to see him.”

Many have tried to duplicate Llewellyn’s technique, but he said the trick is both his particular dexterity and properly diagnosing the patient. “One of my passions is fly fishing and I’ve been tying flies since I was four or five. I’m sure that dexterity of tying flies has tied into my surgery.”

“When I wrote it up in a scientific journal, some people were quite scathing, but the diagnosis is the most important thing,” Llewellyn said. “When people think that the horse has a palate problem they call me. They think it must be his palate, but quite often it’s not. I would say that I only operate on 30 per cent of the horses that people say need surgery.”

Eventing was his late wife Lexie’s passion, so Huw learned to ride on a retired Standardbred named Accountant, built his wife her own eventing course on their Abernant Farm property and even held a couple of events a year for many years — losing “about $50,000 on each one,” he said.

“Our cross-country course was spectacular, but it was too tough for most people and that’s okay. If you want to go to the States to compete, you better come and get over our course or stay at home,” he said, adding one of the jumps was made out of a crashed airplane.

“My father was a bricklayer. I’m just like him, so everything had to be so accurate. They were legitimate fences, not some Mickey Mouse fences, and they were all built really well. I had also been an avid gardener and I had flowers on fences and it was a spectacular thing. I used to even put stripes on the grass – taking the mower and going one way then the other. It was beautiful.”

Llewellyn said Accountant was a pacer that “hated to jump” which made competing a major challenge.

Llewellyn and Accountant, a pacer that “hated to jump.”

“For two years, I never completed an event and all of the international riders all knew me and they’d say, ‘Oh, we have to go watch Huw,’” Llewellyn said. “I remember the first time I actually finished a course there was a big standing ovation. Accountant was a pacer and the judges in dressage couldn’t understand this gait.”

He can laugh about it now. After all, Llewellyn said he’s glad to have survived his near-death experience to lead the richest of lives with horses.