Scott Morrison addressed the AAEP Convention regarding hoof issues and racing-related lameness. In part one of this two-part series, he discussed balance, heel pain and stone bruises. Here he addresses quarter cracks, sheared heels, pedal bone trauma and chemical burns.

Shunted Heel/Sheared Heel

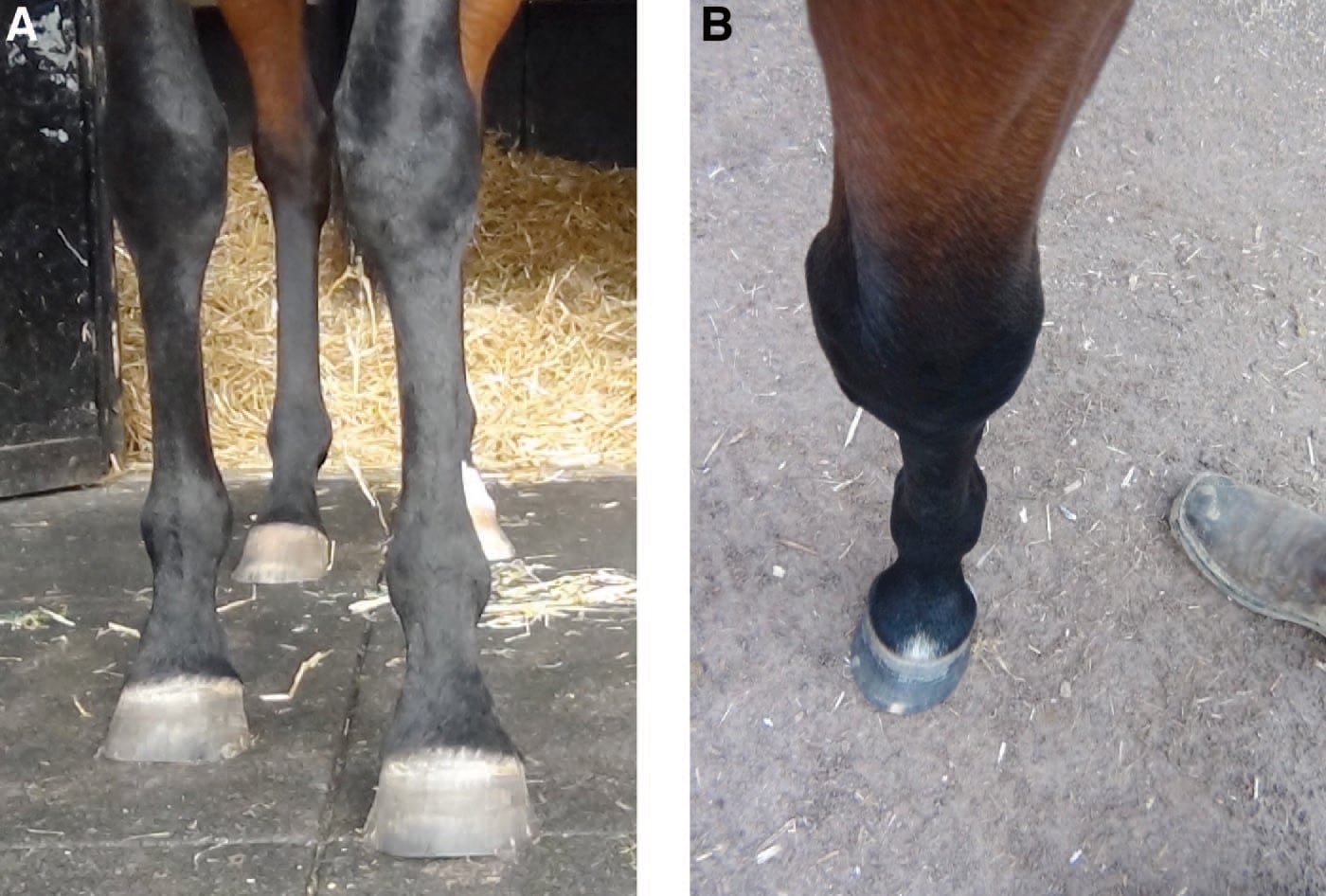

Fig. 5. Sheared medial heel.

By far the most frustrating hoof problem in the racehorse is the reoccurring quarter crack. Often the author hears about a quarter crack hampering the ability of a Triple Crown or other high-profile race contender. Quarter cracks are almost always preceded by a shunted or sheared heel hoof capsule distortion (Fig. 5).

The quarter or heel crack is an acute episode that results from the more insidious, slowly developing condition of the sheared/shunted heel. A shunted or sheared heel is when one heel bulb is displaced proximally. This condition is most commonly the result of long-term overloading of the medial heel quarter. This condition has been described in horses with a base narrow, outward rotational limb deformity; creating the ground reaction force to shift medially during the landing/support phase. These cases typically strike on the lateral aspect of the foot and then load medially.

Fig. 6. Outward rotation of the front limbs. Note the white hairs on the inside of the right front fetlock from interference.

However, in the author’s experience, sheared heels are seen more commonly in racehorses without outward rotation of the limb. Horses with severe outward rotation usually interfere, which commonly affects performance. Sheared heels in upper-level racehorses are more commonly seen in horses that are slightly carpal valgus and have an inward rotation of the distal limb (emanating from the distal metacarpus or pastern). Carpal valgus conformation has been shown to shift the center of pressure medially, and the inward rotation of the distal limb turns the hoof like a dial, putting the medial

heel more in line with the center of force, or directly beneath the cannon bone (Fig. 6).

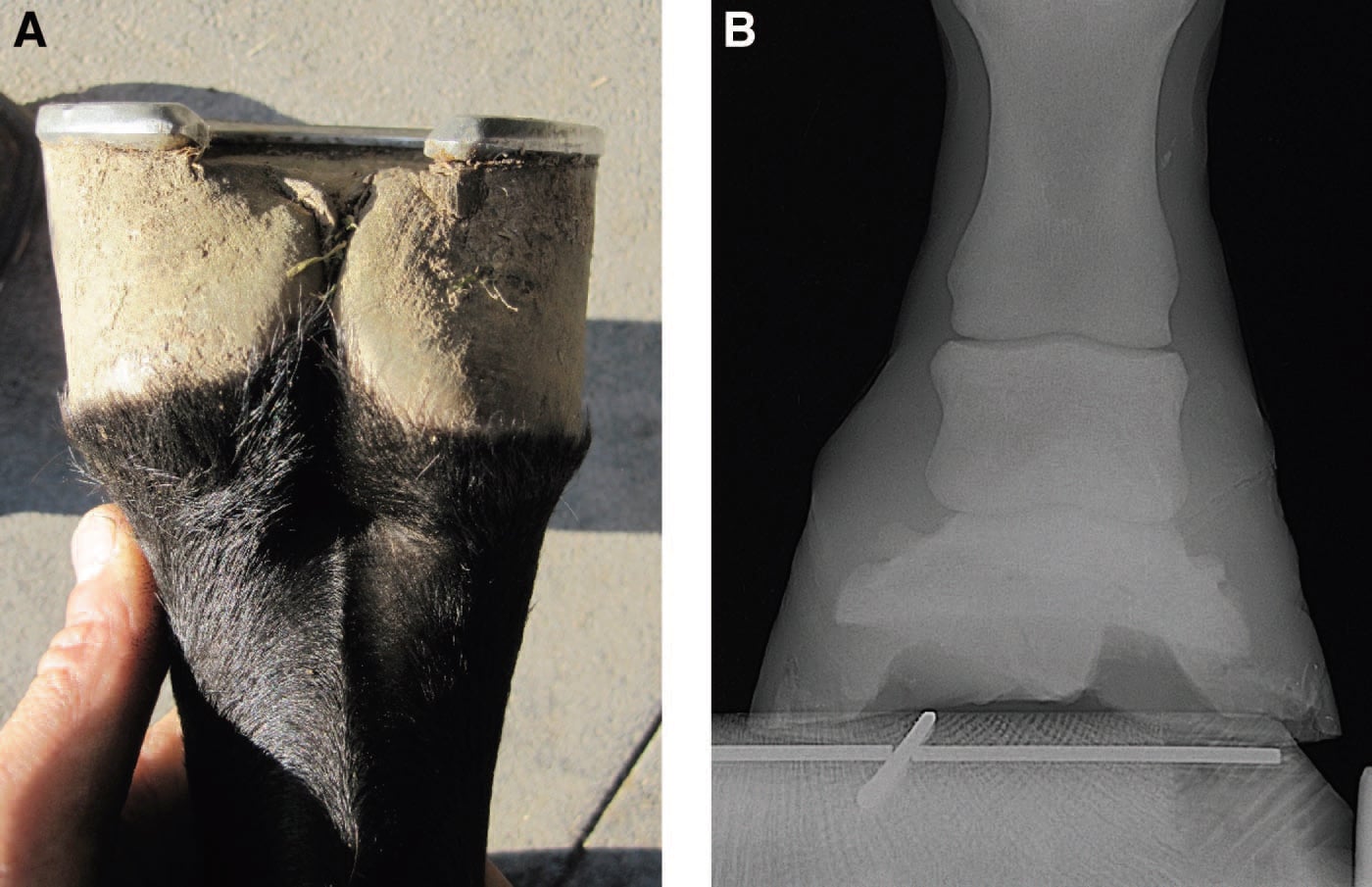

This combination of conformation faults is very common in high-level, successful racehorses. However, it puts increased compressive forces on the medial heel, shunting or displacing it proximally. The increased compression on this region of the foot slows wall and sole growth medially, causing the foot to easily grow out of balance between shoeing cycles. It is very common for these feet to be high on the lateral side and low medially when viewed from the solar surface (Fig. 7). Radiographs taken before trimming and shoeing typically show the coffin bone low medially, especially when evaluated several weeks after shoeing and trimming.

Since 2010, the author has examined 72 sheared heels on Thoroughbred racehorses and recorded the conformation of the limb, with photographs taken directly dorsal to the carpus of each leg affected. Of the 72 sheared heels on the front feet, 70 sheared heels were medial and two were lateral. Both cases with laterally sheared heels were fetlock varus.

Of the 70 medially sheared heels, 60 had a combination of carpal valgus and inward rotation of the distal limb, eight had outward rotation of the limb, one had fetlock valgus, and one had normal conformation (no major conformation fault). Therefore, conformation is very likely to be involved in the development of a sheared heel.

Fig. 7. A: Front view of the left front limb with slight carpal valgus and inward rotation of the pastern. B: Left front limb with slight carpal valgus and inward rotation of the distal cannon bone and pastern.

In the hind end, it is more common to see sheared heels and subsequent quarter cracks in the lateral heel. This is more common in horses that are base-narrow behind and/or fetlock varus in the hind end.

It appears that sheared heels and quarter cracks are most common in the better horses, as higher speed increases ground reaction forces on the foot (the better horses strike the ground harder).

Management of the sheared heel is key in maintaining soundness and preventing the occurrence of quarter cracks. Patching the quarter crack has been described in detail elsewhere and is not covered in this report. Keeping the foot trimmed and balanced is fundamental. Trimming and shoeing on a shorter 3-week schedule may be necessary to prevent severe imbalances.

Fig. 8. A: Medial sheared heel that is also out of balance and high laterally. B: Radiograph of a medial sheared heel case that is high laterally.

The sole surface of the foot is typically divided into quadrants or quarters (medial/lateral toe quarters, medial/lateral heel quarters). If the toe (quarters) are left long, more force is placed on the heel quarters. If the lateral toe and heel quarters are left high, the medial half of the foot is loaded.

Although studies show that artificially elevating the lateral aspect of the hoof shifted the center of pressure laterally, it is unknown if this holds true in cases that naturally grow faster laterally and grow out of balance. In practice, the author sees more signs of compression and damage on the medial side as the lateral wall grows higher and the foot becomes more imbalanced. Therefore, to unload the medial quarter, the author trims the toes as short as possible and lowers the lateral heel so that the solar surface of the foot is perpendicular to the long axis of the pastern.

It is important to fit with a shoe that is centered on the coffin joint, so that the widest part of the foot is in the center of the shoe and the heel of the shoe is at least at the widest part of the frog. Too much length of the toe combined with a medial-lateral imbalance can overload the medial quarter.

Foot trimmed and shod perpendicular to the long axis of the pastern.

Because the sheared heel results from overloading and displacement of the hoof wall/heel bulb, methods to unload and allow the wall to drop back down are necessary for successful management. This can be performed most effectively with the use of a heartbar, bar shoe, or stabilizer plate, which transfers weight onto the base of the frog (Fig. 8). The wall beneath the sheared heel can then be floated off the shoe so that the displaced wall can drop down.

Many trainers do not like the added weight and decreased traction created with a bar shoe; therefore this shoeing prescription sometimes can have poor compliance. One option is to train in the bar shoe and switch to a normal race plate on race day or shortly before. Another option used in the author’s practice with significant success is the use of temporary orthotics. This is when a two-part elastomer dental impression putty is used to make a custom orthotic or arch support for each foot. The removable orthotics are placed into the feet and wrapped in place with Vetwrap (Fig. 9). The orthotics can be removed for training and placed back in the foot when the horse is in the stall.

Fig. 9. A, Case with slight carpal varus and significant inward rotation of the pastern on the right front. B, Same case, viewed from the front; note the offset appearance of the hoof and pastern. C, Radiograph of the same right front foot.

A: The two-part elastomer is mixed and applied to the sole surface of the foot. B: It is then wrapped onto the foot, and the horse stands on a flat surface until elastomer sets up. C and D: The orthotic is removed and trimmed up so that it can easily be inserted and removed daily.

The orthotics provide arch support and help unload the perimeter wall to strengthen the arch and allow the shunted wall to drop. Bar shoes or temporary orthotics, combined with shortened balanced trimming intervals, have significantly decreased the occurrence of quarter cracks and improved the sheared heels in the author’s practice.

Although not always feasible, letting these cases go barefoot when possible is very effective in improving the sheared heel. Often the medial heel sole depth is so thin that these cases need shoes to resume training.

Pedal Bone Fractures

Secondary to weak heel structures and high loads placed on the heels is trauma to the coffin bone, including fracture of the wing. Wing fractures are the most common pedal bone fracture the author sees in the Thoroughbred racehorse.

It has been reported that wing fractures are more common laterally in the left front and medially in the right front. However, in the author’s experience, lateral wing fractures are more commonly seen in the right and left front feet. This could be because most horses land lateral heel first at higher speeds, and fractures of the wing may occur during initial impact.

Clinical signs are acute severe lameness. Radiographs taken usually show the fracture line immediately. Occasionally, the fracture line is not evident until there is demineralization and lysis at the margins of the fracture. If a diagnosis is not evident on initial radiographs and a fracture is suspected, then follow-up radiographs are usually repeated in 3 to 5 days.

Most wing fractures require 6 to 8 months to heal. Treatment consists of bar shoe with sole support or a wall cast. Most cases are stall rested for 2 to 3 months and hand-walked until the fracture has healed.

Some cases will not heal completely and may only heal with a fibrous union, in which a radiolucent line persists. Adequate stabilization with shoeing and stall rest will probably result in radiographic healing.

Subchondral Bone Trauma/Contusions to the Pedal Bone

Cases with contusion to the pedal bone or subchondral bone present similar to a fractured pedal bone. However, follow-up radiographs fail to reveal a diagnosis. Cases are usually diagnosed on magnetic resonance imaging or nuclear scintigraphy.

Treatment is shoeing to absorb concussion and protect the solar surface and stall rest, combined with aspirin and isoxsuprine until digital pulses have returned to normal and the horse walks soundly. Some cases may resolve in days and some severe cases can take months.

Chemical Burns

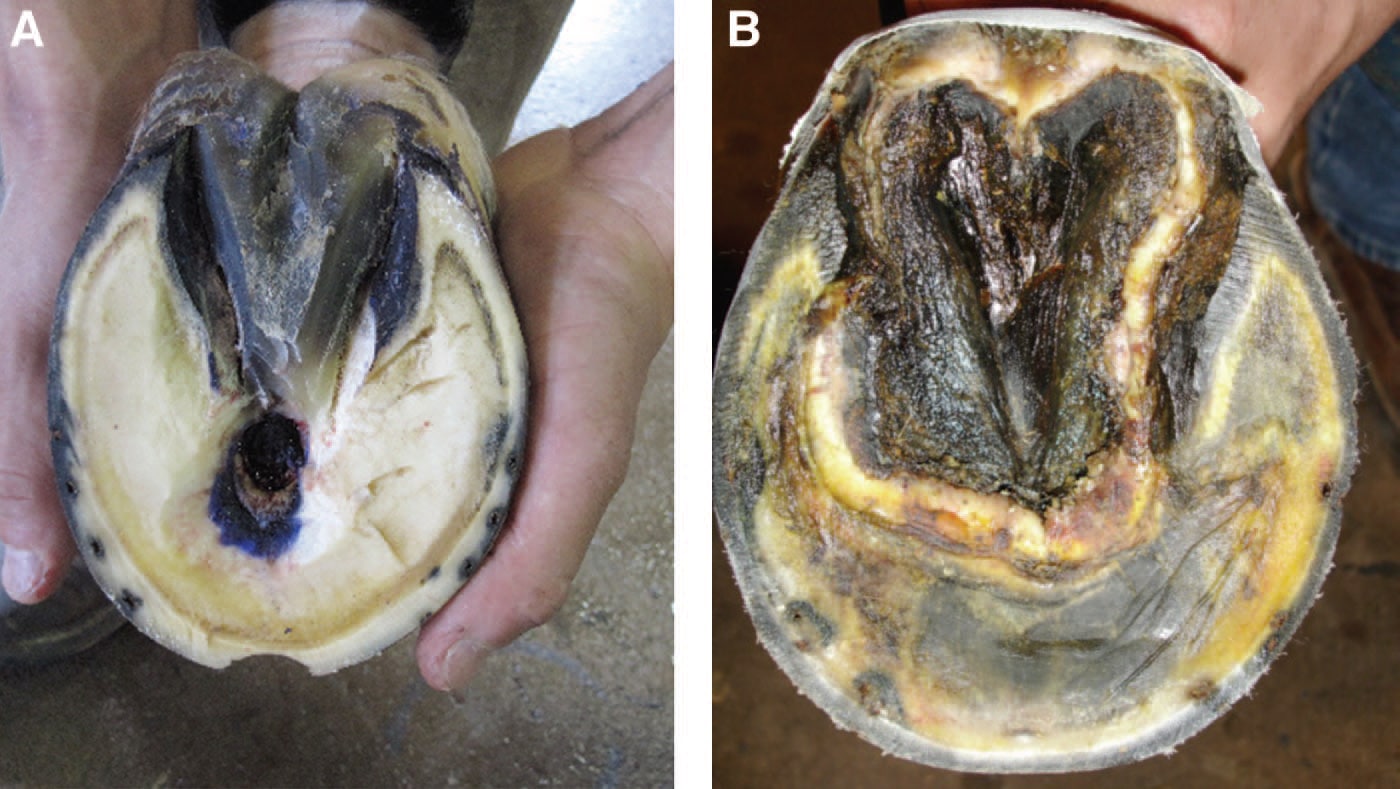

A: Chemical burn to the sole region. This burn extended down to the solar surface of the pedal bone and required surgical debridement to heal. B: Chemical burn to the frog, which involved the digital cushion, deep digital flexor tendon, and navicular bone. This horse was euthanized.

Treating infections or exposed sensitive tissue in the foot is not in the scope of this lecture, but mismanagement and topical medication on the sensitive tissue of the foot is so prevalent on the racetrack that it should be mentioned here.

It is very common to see cases that have had sensitive tissue exposed by a subsolar abscess/infection or a quarter crack that has been treated at the racetrack with caustic materials in an effort to “harden” and heal over the defect. Most of the compounds are formulated for treating thrush and contain iodine and formalin and usually contain purple dyes to indicate the presence of medication. These compounds are made to treat superficial infections of the frog and have no place in treatment of exposed sensitive tissue or coria. Many quarter cracks are first treated with these substances to “dry them out” before patching. The iodines and formalin damage the sensitive submural tissues or corium/lamellar, creating scar tissue. This weakened, damaged tissue in the bed of the crack is probably part of the reason for the high prevalence of crack reoccurrence.

Similarly, the author has seen numerous cases of exposed corium of the sole chemically burned. Severe cases can involve the solar surface of the coffin bone and the deep digital flexor tendon, creating career-ending or life-threatening damage. Client education in proper use and misuse of topical agents is imperative to prevent misuse of these compounds.

***

Scott Morrison, DVM, is a podiatrist and shareholder at Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, where he sees a variety of foot and lameness-related cases. He graduated from Virginia Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine in 1999.