The importance of foot shape and balance in high-performance racehorses is paramount to maintaining soundness and optimal performance. Functionally adapted for speed and efficient use of energy, the Thoroughbred foot is light and lacks the mass for protection commonly seen in other heavier-boned breeds. The relatively thin walls and soles of the Thoroughbred foot make it more susceptible to injury and hoof capsule distortion. Hoof capsule distortion refers to hoof abnormalities such as flares, cracks, under-run, collapsed, and sheared heels—all of which result from long-term abnormal weight distribution on the foot. Distortions affect function and have been correlated to musculoskeletal injuries and lameness.

The racehorse practitioner is often presented with an acute or chronic foot problem to manage. Having knowledge of the etiology of the more common foot problem will help formulate a successful treatment plan to heal the acute condition, return the horse back to soundness, and prevent reoccurrence.

Without the proper knowledge of the entire problem, most foot problems are quickly fixed and patched up, and the underlying hoof capsule distortion is never effectively addressed. Therefore, it is likely to reoccur.

Balance

Balance is the term used when describing the shape, angle, and spatial arrangement of anatomical structures of the foot. Learning how to evaluate a foot and detect imbalance or overloaded regions of a foot are important for formulating a treatment plan.

Although some properties of balance will vary with limb conformation and are subjective, it is generally accepted that balanced Thoroughbred feet possess the following characteristics:

- Even distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint space on anterior-posterior standing radiograph

- Straight hoof pastern axis

- Center of the DIP joint or widest part of foot should be located in the center of the weightbearing

surface of the shoe in the sagittal plane - Palmar angle of pedal bone should be between 2° to 5°

- Heel position should be located at the widest part of the frog

- Heel angle should be within 5° of toe angle

- Solar surface of foot perpendicular to long axis of pastern bone in the sagittal plane

- Even hoof wall growth from all regions of the coronary band

Fig. 1. Common racehorse foot with negative palmar angle and thin sole depth at heel.

The typical Thoroughbred conformation of a longer, more sloping pastern places more force on the heel region. Repetitive speed training in racehorses decreases hoof angle over time, and, as hoof angle decreases, more stress is placed on the heel region. Therefore, low hoof angles and increased stress on the heel region can become a self-perpetuating cycle if proper intervention is not implemented to reverse the downward trend of the foot (Fig. 1).

The heel region is usually the first part of the foot to display a distortion because it is generally made up of softer, more compliant structures than is the toe. Hoof capsule distortions occur slowly over time and are the result of long-term abnormal weight-bearing.

The horse’s foot is capable of handling huge impact forces without structurally collapsing. This is because when a horse is traveling, the moving foot fills with blood during the swing phase, probably from centrifugal force and creating turgor pressure. This fluid in closed spaces may help support the architecture of the foot during ground impact, thus allowing the foot to withstand high impact forces.

Fig. 2. Properly glued shoe; note that there is very little glue on the sole, and the frog sulci are not obstructed.

Most hoof capsule deformities (under-run, collapsed heels) slowly develop over time. The author believes that most of these distortions occur while the foot is semi-static (while the horse is just standing around). Racehorses spend 22+ hours a day standing in a straw-bedded stall. It is during this period that the foot is mostly dependent on the architecture of the foot tissues for support.

Long-term, low magnitude loading creates distortion rather than short-term, high-magnitude force. Horses standing in a stall with little arch/sole support slowly fatigue the integrity of the capsule and propagate distortions. The arch of the sole slowly flattens, the heels become under-run, and perhaps a heel bulb becomes sheared or shunted proximally. The insidious nature of a hoof capsule distortion slowly compromises the foot, rendering it more susceptible to an acute injury.

Heel Pain in the Front Limb

In the author’s experience, the most common site of heel pain in the racehorse is pain in the medial heel region of the front feet. Pain in this region can originate from a variety of sources: bruising of the sensitive sole, osteitis of the wing of the coffin bone (pedal osteitis), submural pain from sensitive laminae/wall separations, sheared or shunted heels, and quarter/heel cracks. Pain in the medial heel is so prevalent that rarely does the author fail to find sensitivity over the medial heel/bar region on a routine hoof tester exam of a racehorse.

The etiology of heel pain in the racehorse is multifactorial; conformation, farriery, track conditions, and management all play major roles. Even though common causes of heel pain can be seen simultaneously as a syndrome, we will discuss them separately.

Fig. 3. A: Properly fitted race plate, with heel checks and unobstructed frog sulci. B: Race plate fitted too tightly in the heels, with no heel checks. The frog sulci are obstructed and likely to trap dirt, causing bruising.

Heel Bruise/Stone Bruise

A common reason for a racehorse to be scratched from a race or given time off is for a stone bruise or bruised foot. The author finds this cause of lameness has always been surprising. Racehorses generally are housed, hot-walked, trained, and raced on fairly good footing, with little chance for a stone or hard terrain to directly bruise the foot. Therefore, the term “stone bruise,” in most cases is a misnomer.

Bruising of the foot can be caused in three different ways: (1) sole pressure from the shoe or glue. This can be from a shoe that was fitted too small or too tight, creating sole pressure, or from a shoe that has been left on too long, allowing the heels to overgrow or expand over the shoe creating sole pressure. (2) Gluing shoes with acrylic has become common practice in racehorses with brittle, poor-quality walls.

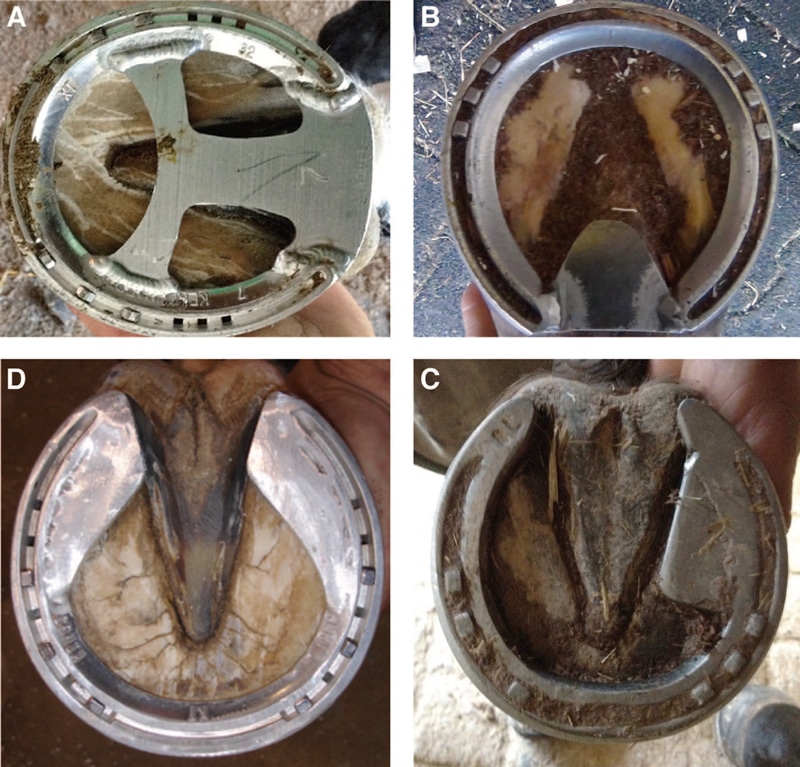

Fig. 4. A: Shoe with a stabilizer pad welded in for support and protection. B: Heartbar welded into a steel training plate. C: Onion heel shoes, used to protect the bars. D: Unilateral onion heel, used to protect the wing of the pedal bone and bar.

Care must be taken in using very little glue and not allowing the glue to set up on the pliable solar surface. The acrylic, once set up, can become very firm, creating sole pressure or pressure on the soft solar heel bulbs. If the glue is allowed too high up the wall near the heel bulb, then, during speed training when the heel bulb compresses, the top edge of the glue can pinch the heel bulbs, creating soreness (Fig. 2).

The third cause of a heel bruise is an excessive heel check on the shoe. That is, the branches of the shoe wrap around too tightly, covering up the medial and lateral sulci of the frog and don’t allow clearance

of the footing through the sulci. The branch of the shoe will allow footing to ball up and become tightly

compacted as it is forced into the sulci at high speeds during the sliding phase of impact. Rapid deceleration of the foot will drive the track substrate into the sulci like a wedge, creating bruising.

This is probably the most common cause of medial heel bruising (Fig. 3). Repetitive bruising of the sole or an acute severe bruise can cause inflammation of the bone (pedal osteitis). Pedal osteitis is most successfully diagnosed by nuclear scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging, which can show active inflammation and edema. Less accurate diagnostics are radiographs that may show the chronic change of demineralization and loss of the normal, smooth contour of the solar border of the pedal bone (Fig. 4).

This, along with positive response to hoof testers and diagnostic analgesia, is probably sufficient to make a diagnosis in a young horse; however, it is questionable how accurate the radiographic changes are without the aid of diagnostics that show the physiology of acute inflammation.

Pedal osteitis can be seen more commonly in the heel region of a low-heeled foot, but it can also be seen in the toe region, particularly in upright or club-footed horses. Severe trauma to the margins of the pedal bone can cause marginal rim fractures. These cases are typically severely acutely lame and then improve over a few days with stall rest. These horses require at least 60 to 90 days of rest to heal before being gradually reintroduced back into training.

Shoeing is for protection, shock absorption, and ease of the breakover, and to decrease tension on anterior laminae against the bone fragments in the toe region. A wide web shoe, or a shoe and pad, with a rolled/rockered toe are indicated. For pedal osteitis of the palmar/plantar process, a shoe with protection of the heel quarters is indicated. Shoe with pad, stabilizer plate, onion heel shoe, or bar

shoe are indicated.

Once the inflammation has resolved, most cases will require special shoeing when they go back into training because reoccurrence is very common. Training in an onion heel shoe, bar shoe, or spider plate is usually effective.

Next time: Quarter cracks, sheared heels, pedal bone trauma and chemical burns.

***

Scott Morrison, DVM, is a podiatrist and shareholder at Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, where he sees a variety of foot and lameness-related cases. He graduated from Virginia Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine in 1999.